This is a work in progress and is subject to revision and update.

It represents a very small portion of the research I have conducted over several years regarding the events that took place in the Philippine Islands immediately prior to and during the opening days of World War II as well as the experiences of those who became prisoners of the Japanese. Ultimately, this research will lead to the publishing of a book.

If you are a veteran of World War II in the Philippines during 1941 and 1942, your story needs to be told and I ask that you contact me.

This is a story of death and survival as experienced by the American military who were stationed in the Philippine Islands at the outbreak of World War II.

Having arrived in Manila in August 1941, and with the possibility just over the horizon the United States would become involved in a war in the Pacific, one small group of American soldiers were soon to experience a horrific set of events that, for many of the survivors, would torment them for the rest of their lives.

By 1940, it became apparent the United States might be drawn into a war with the Japanese in the Pacific. In order to provide a means of early warning for the Philippines, a radar set had been placed in operation at Iba Field on the west coast of Luzon Island. A similar radar set was also in use by the U.S. Army on Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands.

In November and early December 1941, the men of the Aircraft Warning Company at Iba Field began picking up unidentified aircraft off the coast of Luzon on their radar set. On several occasions, planes from the pursuit squadron at Iba had been sent to intercept the radar contacts, but were unable to do so.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked United States military installations on Oahu. Their attack crippled the U.S. Navy's Pacific Fleet, the majority of which was at anchor, moored or drydocked in Pearl Harbor, on what was anticipated to be a quiet Sunday morning like so many such days in the past. Instead, it would turn out to be a day of dying and destruction as well as a day of heroic acts to save the ships and their crews. The photos below show USS SHAW (DD-373) with its forward magazine exploding and USS WEST VIRGINIA (BB-48) on fire as a result of the Japanese attack.

Across the expanse of the Pacific Ocean, and on the other side of the International Date Line, American forces in the Philippine Islands were just hours away from a similar experience.

The Iba radar scope was glowing with contacts in the early morning hours of December 8, 1941. Before the end of that day, the world would be much different for the men of the Aircraft Warning Company.

Survivors of the soon to be fought battles on Bataan and the relentless shelling of Corregidor would next experience some of the most inhumane treatment as a prisoner of war that one human being could impose on another. For those who ultimately survived three and an half years of captivity, many would suffer the torments of those experiences in silence for the rest of their lives.

Following the unprovoked attack by the Japanese against U.S. forces in Hawaii and the Philippines, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Declaration of War against Japan on December 8, 1941.

Thousands of Americans readily joined the military following the Japanese attacks in the Pacific. Their vacant jobs were quickly filled by thousands of women who wanted to do their part to win the war. Some of those women were pilots who ferried bombers and fighter planes to their shipment ports or to overseas locations. Others worked as machinists and electricians in defense plants or as welders and riveters in shipyards and in numerous other jobs in support of the war effort. America's quick mobilization of its vast industrial capacity would lead to the eventual winning of this war, but many thousands of those who were captured by the Japanese in the Philippines and elsewhere in the Pacific theater would not live to see the war's end.

Stories of atrocities committed by the Japanese against military and civilian prisoners of war would reach the highest levels of the U.S. government during the ensuing months and years of the war.

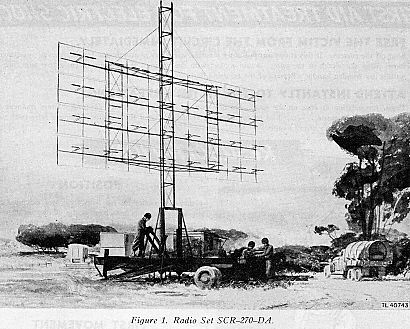

The AN/SCR-270 early warning radar set was the result of several years of research and development at the U.S. Army Signal Corps laboratories in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey as well as at Camp Evans in Belmar, New Jersey.

A working model of a radar (the AN/SCR-268) was successfully demonstrated in May 1937 at Fort Monmouth. Following that success, the AN/SCR-270 (a mobile radar) and the AN/SCR-271 (a non-mobile version of the SCR-270) were developed and placed into use by the U.S. Army.

The 'AN' portion of the equipment designation indicates it is dual use equipment meant for use by the Army and Navy; the SCR portion stands for 'Signal Corps Radio'. The term 'radio' was used instead of 'radar' to describe the equipment as a means of deception to help mask the ongoing classified research and development being conducted into the acquisition and tracking of objects at a distance.

Men from the U.S. Army Signal Corps attended radar school at Fort Monmouth where they received instruction in operating and maintaining the equipment.

The SCR-270 radar set was a somewhat bulky device consiting of a large antenna, a power source and an equipment van. Its advantage was the fact that it was mobile and therefore could be moved from place to place as the situation required.

In August 1941, 30 men, composing the Air Warning detachment, arrived in Manila. This was followed in early October with the arrival of the radar set they would be operating (the AN/SCR-270). After a brief period, during which they assembled, calibrated and tested the radar, the detachment was sent to Iba Field. It was there they would set up and place in operation the only working early warning radar set west of Hawaii.

The radar group at Iba was led by an army lieutenant and my father was the chief radar operator. The Aircraft Warning Company at Iba was composed of the following: (the list which follows will identify the men in the radar company)

On December 8, 1941, the Iba radar gained contact on what were believed to be Japanese aircraft. These planes were enroute to attack Clark Field. This would be followed by the bombing of Iba, which resulted in the destruction of the radar equipment and the death of five men of the Aircraft Warning Company as well as several others from the field's pursuit squadrons.

In addition to strikes by Japanese aircraft against U.S. military facilities, their forces would conduct amphibious landings over the next several days.

The fight for the Philippines had begun.

The Japanese anticipated victory in the Philippines would be theirs in just a matter of weeks. This would not be the case.

The tenacity of the American military and their Filipino counterparts would slow the Japanese timetable to a crawl. As a result, Tokyo would put intense pressure on the Japanese commander in charge of the Philipine invasion forces. Because the Americans and Filipinos fought so hard and stymied their plans, the Japanese would be forced to introduce more troops to their campaign in the Philippines.

The American and Filipino troops fought the Japanese under quite adverse conditions, including ever diminishing food and medical supplies. The daily food ration was continually cut and as a result, many of the troops became severly malnourished and were barely able to function in a fighting capacity.

On December 23, 1941, coincident with the shift of General Douglas MacArthur's headquarters from Manila to Corregidor, General Wainwright was directed to withdraw his Luzon forces to the Bataan Peninsula.

Ultimately, the Japanese onslaught would push the American and Filipino troops deep onto Bataan. With food supplies nearly exhausted, and battle weary troops trapped, Major General King, who had been placed in charge of the Bataan forces, saw no other choice but to surrender his 70,000 troops to the Japanese on April 9, 1941. The night prior to the surrender, about 2000 troops managed to reach Corregidor by barge and boat.

The Japanese had not anticipated the surrender of such a large force. They fully anticipated the American troops would continue to fight until the last man was killed. Now they had 70,000 prisoners on their hands and no real plan to effectively deal with them. It was however decided that the prisoners would be moved from Bataan in order for the Japanese to continue their assault on Corregidor and other fortifications in Manila Bay.

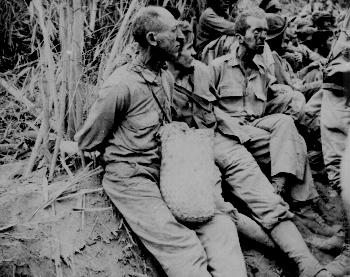

Those who were captured on Bataan were forced to march approximately 65 miles, from the southern end of Bataan to San Fernando Pampanga, where they were packed in boxcars and transported 10 miles to Capas. From there, they walked 7 miles to Camp O'Donnell. The march from Bataan was done under very adverse conditions, with little to no food or water being provided during the continuous movement. The photo to the left shows American prisoners along the march route with their hands tied behind their backs.

Many American and Filipino troops would not complete the march. Those who attempted to drink water from ditches or animal watering holes along the roadway were shot. Those too weak to continue the march, fell by the roadside and were shot or bayonetted. Prisoners who attempted to assist a fellow soldier were often shot or bayonetted as well. The route of the march to O'Donnell was lined with the bodies of dead American and Filipino troops.

This event became known as the March of Death, then later as the Bataan Death March.

Those on Corregidor hoped they could hold out until a rescue force arrived. This would not be the case. The American Pacific fleet had been decimated at Pearl Harbor and any relief forces that could be assembled would have to travel to the Philippine Islands virtually unprotected. Any supplies that did arrive were primarily brought in by submarine.

After unloading their cargo, those submarines were used evacuate the nurses and certain military and civilian personnel. In March 1942, General MacArthur was ordered to leave Corregidor for Australia. General Jonathan Wainwright then took command of Corregidor as well of all U.S. forces in the Philippines.

On May 5, 1942, the Japanese conducted an amphibious landing on Corregidor. Fierce battles ensued, but ultimately General Wainwright had to decide whether to fight to the last man or surrender. On May 6, 1942, Corregidor and its 11,000 troops were surrendered to the Japanese. The photo to the left shows surrendering American and Filipino troops leaving the Corregidor tunnel complex.

The Japanese gathered all the prisoners in one area, where they remained for several days after which they were placed aboard ships and transported across the bay to Manila. From the docks they were marched through town to Bilibid Prison.

A few days after their arrival at Bilibid Prison, the Americans were tightly packed into railroad cars and transported to Cabanatuan.

The Cabanatuan prison camp presented its own challenges to survival for the thousands of troops who were sent there. Food was scarce and medical supplies, other than what they had managed to conceal following the surrender, were virtually non-existant. Various diseases ran rampant through the camp and many died. Each day a procession of litter bearers left the camp to bury those who had died during the previous night.

The photo to the left shows prisoners carrying their dead to be buried. In some sources, this photo is labeled as being that of American prisoners carrying those who could no longer make the journey from Bataan on foot. Other sources portray the photo as that of Filipino's carrying their dead. In either case, the face masks the bearers are wearing portray a situation involving death.

Since Japan had mobilized an enormous military force to carry out its plans for expansion in the Pacific, their industrial complex was suffering. There simply was not enough manpower remaining in Japan to sustain production. It was decided to use passenger and cargo ships, which had taken troops and supplies to the warfront, to bring prisoners of war to Japan.

These ships made numerous trips from the Philippines and Formosa to Japan. Their human cargo was packed tightly into the empty holds. Food and water were in short supply and sanitation facilities were inadequate for the number of prisoners onboard. Men who died during the journey were ordered thrown overboard.

To make matters worse, the ships were not marked as carrying prisoners of war. As a result, many were torpedoed by American submarines and straffed by American aircraft. One of these ships, the Arisan Maru, with 1800 prisoners onboard, was torpedoed and only 8 survived.

These ships were known as 'hellships' for they truly were hell for those on board.

A list of those ships, by name, and with their sailing dates can be found in the Appendix.

As prisoners of war, they thought constantly of a better life, especially the life which had existed prior to the war. In prison camp, some prisoners would hold 'classes' in such subjects as astronomy or geography for their fellow prisoners to keep their mind off their present state of circumstances.

The men of Bataan and Corregidor, having come to Japan from the tropical climate of the Philippines, did not possess winter clothing and many were without shoes when they arrived. Upon their arrival, they were forced to walk through crowds of Japanese who taunted, hit and threw objects at them. Even when there was snow on the ground, they were required to march to their destination regardless of whether or not they wore shoes. Those too weak to move were, on one occassion, left on the pier and never seen again.

It took a great deal of courage and self-determination to keep going day after day. The amount of food goven the prisoners was inadequate, the living quarters were unheated except for perhaps an hour or so a day, their clothing was in tatters, and many were sick. To make matters worse, the men marched to often distant work sites where they toiled in twelve to fourteen hour shifts in the steel mills, shipyards and coal mines of Japan. In spite of the adversity they faced, many found the will to hang on in spite of the conditions they were under. Some prisoners, unfortunately, would not see the end of the war and freedom, because they either gave up or were starved or beaten to death by their captors.

The leaders of Japan's major industrial corporations, faced with a severe manpower shortage due to the mobilization of factory workers for military duty, had influenced the Japanese government to bring prisoners of war to Japan so they could be put to work.

Over forty Japanese corporations used American and British prisoners of war for their own enrichment. Familiar names among those corporations are Kawasaki (heavy industries), Hitachi (shipbuilding) and Mitsubishi (heavy industries/chemical/mining). None of these corporations were ever brought before a war crimes tribunal for their actions, yet many of their executives were directly responsible for the deaths of hundreds of prisoners of war being held in Japan.

The following is a partial list of reference material being used to develop this document:

Bartsch, William H. Doomed at the Start: American Pursuit Pilots in the Philippines, 1941-1942. College Station, Texas: Texas A & M University Press, 1992.The following links provide additional information:

American Battle Monuments CommissionThis section will contain information to supplement the various chapters shown in the Table of Contents.

If you fought in the Philippines during 1941-1942, I would like to document your experiences. Please contact me.